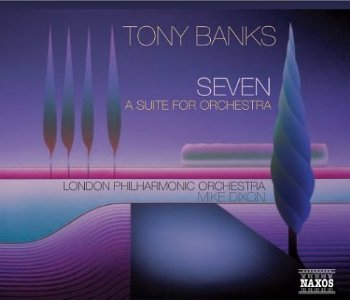

| Artist: | Tony Banks |

| Title: | Seven (A Suite for Orchestra) |

| Released: | 2004.04.20 |

| Label: | Naxos |

| Time: | 57:39 |

| Producer(s): | Nick Davis, Tony Banks |

| Appears with: | Genesis, Peter Gabriel, Steve Hackett, Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford, Ray Wilson |

| Category: | Classical |

| Rating: | ***....... (3/10) |

| Media type: | CD |

| Purchase date: | 2004.05.06 |

| Price in €: | 6,99 |

| Web address: | www.genesis-music.com |