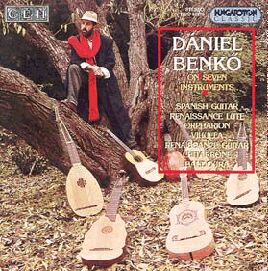

| Artist: | Benkö Dániel |

| Title: | Hét hangszeren - On Seven Instruments |

| Released: | 1992 |

| Label: | Hungaroton Classics |

| Time: | 55:16 |

| Producer(s): | |

| Appears with: | |

| Category: | Classic |

| Rating: | ******.... (6/10) |

| Media type: | CD |

| Purchase date: | 1999.05.14 |

| Price in €: | 7,63 |

| Web address: | www.hungaroton.hu |