The Yardbirds are mostly known to the casual rock fan as the starting point for three of the greatest British rock guitarists: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page.

Undoubtedly, these three figures did much to shape the group's sound,

but throughout their career, the Yardbirds were very much a unit,

albeit a rather unstable one. And they were truly one of the great rock

bands; one whose contributions went far beyond the scope of their half

dozen or so mid-'60s hits ("For Your Love," "Heart Full of Soul,"

"Shapes of Things," "I'm a Man," "Over Under Sideways Down,"

"Happenings Ten Years Time Ago"). Not content to limit themselves to

the R&B and blues covers they concentrated upon initially, they

quickly branched out into moody, increasingly experimental pop/rock.

The innovations of Clapton, Beck, and Page redefined the role of the

guitar in rock music, breaking immense ground in the use of feedback,

distortion, and amplification with finesse and breathtaking virtuosity.

With the arguable exception of the Byrds, they did more than any other

outfit to pioneer psychedelia, with an eclectic, risk-taking approach

that laid the groundwork for much of the hard rock and progressive rock

from the late '60s to the present.

The Yardbirds are mostly known to the casual rock fan as the starting point for three of the greatest British rock guitarists: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page.

Undoubtedly, these three figures did much to shape the group's sound,

but throughout their career, the Yardbirds were very much a unit,

albeit a rather unstable one. And they were truly one of the great rock

bands; one whose contributions went far beyond the scope of their half

dozen or so mid-'60s hits ("For Your Love," "Heart Full of Soul,"

"Shapes of Things," "I'm a Man," "Over Under Sideways Down,"

"Happenings Ten Years Time Ago"). Not content to limit themselves to

the R&B and blues covers they concentrated upon initially, they

quickly branched out into moody, increasingly experimental pop/rock.

The innovations of Clapton, Beck, and Page redefined the role of the

guitar in rock music, breaking immense ground in the use of feedback,

distortion, and amplification with finesse and breathtaking virtuosity.

With the arguable exception of the Byrds, they did more than any other

outfit to pioneer psychedelia, with an eclectic, risk-taking approach

that laid the groundwork for much of the hard rock and progressive rock

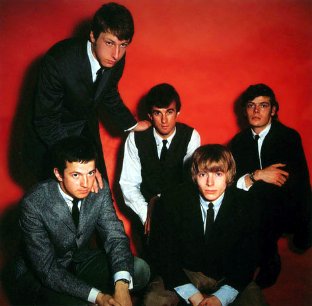

from the late '60s to the present.No one could have predicted the band's metamorphosis from their humble beginnings in the early '60s in the London suburbs as the Metropolis Blues Quartet. By 1963, they were calling themselves the Yardbirds, with a lineup featuring Keith Relf (vocals), Paul Samwell-Smith (bass), Chris Dreja (rhythm guitar), Jim McCarty (drums), and Anthony "Top" Topham (lead guitar). The 16-year-old Topham was only to last for a very short time, pressured to leave by his family. His replacement was an art-college classmate of Relf's, Eric Clapton, nicknamed "Slowhand."

The Yardbirds quickly made a name for themselves in London's rapidly exploding R&B circuit, taking over the Rolling Stones' residency at the famed Crawdaddy club. The band took a similar guitar-based, frenetic approach to classic blues/R&B as the Stones, and for their first few years they were managed by Giorgio Gomelsky, a colorful figure who had acted as a mentor and informal manager for the Rolling Stones in that band's early days.

The Yardbirds made their first recordings as a backup band for Chicago blues great Sonny Boy Williamson, and little of their future greatness is evident in these sides, in which they were still developing their basic chops. (Some tapes of these live shows were issued after the group had become international stars; the material has been reissued ad infinitum since then.) But they really didn't find their footing until 1964, when they stretched out from straight R&B rehash into extended, frantic guitar-harmonica instrumental passages. Calling these ad hoc jams "raveups," the Yardbirds were basically making the blues their own by applying a fiercer, heavily amplified electric base. Taking some cues from improvisational jazz by inserting their own impassioned solos, they would turn their source material inside out and sideways, heightening the restless tension by building the tempo and heated exchange of instrumental riffs to a feverish climax, adroitly cooling off and switching to a lower gear just at the point where the energy seemed uncontrollable. The live 1964 album Five Live Yardbirds is the best document of their early years, consisting entirely of reckless interpretations of U.S. R&B/blues numbers, and displaying the increasing confidence and imagination of Clapton's guitar work.

As much they might have preferred to stay close to the American blues and R&B that had inspired them (at least at first), the Yardbirds made efforts to crack the pop market from the beginning. A couple of fine studio singles of R&B covers were recorded with Clapton that gave the band's sound a slight polish without sacrificing its power. The commercial impact was modest in the U.K. and non-existent in the States, however, and the group decided to change direction radically on their third single. Turning away from their blues roots entirely, "For Your Love" was penned by British pop/rock songwriter Graham Gouldman, and introduced many of the traits that would characterize the Yardbirds' work over the next two years. The melodies were strange (by pop standards) combinations of minor chords; the tempos slowed, speeded up, or ground to a halt unpredictably; the harmonies were droning, almost Gregorian; the arrangements were, by the standards of the time, downright weird, though retaining enough pop appeal to generate chart action. "For Your Love" featured a harpsichord, bongos, and a menacing Keith Relf vocal; it would reach number two in Britain, and number six in the States.

For all its brilliance, "For Your Love" precipitated a major crisis in the band. Eric Clapton wanted to stick close to the blues, and for that matter didn't like "For Your Love," barely playing on the record. Shortly afterward, around the beginning of 1965, he left the band, opting to join John Mayall's Bluesbreakers a bit later in order to keep playing blues guitar. Clapton's spot was first offered to Jimmy Page, then one of the hottest session players in Britain; Page turned it down, figuring he could make a lot more money by staying where he was. He did, however, recommend another guitarist, Jeff Beck, then playing with an obscure band called the Tridents, as well as having worked a few sessions himself.

While Beck's stint with the band lasted only about 18 months, in this period he did more to influence the sound of '60s rock guitar than anyone except Jimi Hendrix. Clapton saw the group's decision to record adventurous pop like "For Your Love" as a sellout of their purist blues ethic. Beck, on the other hand, saw such material as a challenge that offered room for unprecedented experimentation. Not that he wasn't a capable R&B player as well; on tracks like "The Train Kept A-Rollin'" and "I'm Not Talking," he coaxed a sinister sustain from his instrument by bending the notes and using fuzz and other types of distorted amplification. The Middle Eastern influence extended to his work on all of their material, including his first single with the band, "Heart Full of Soul," which (like "For Your Love") was written by Gouldman. After initial attempts to record the song with a sitar had failed, Beck saved the day by emulating the instrument's exotic twang with fuzz riffs of his own. It became their second transatlantic Top Ten hit; the similar "Evil-Hearted You," again penned by Gouldman, gave them another big British hit later in 1965.

The chief criticism that could be levied against the band at this point was their shortage of quality original material, a gap addressed by "Still I'm Sad," a haunting group composition based around a Gregorian chant and Beck's sinewy, wicked guitar riffs. In the United States, it was coupled with "I'm a Man," a re-haul of the Bo Diddley classic that built to an almost avant-garde climax, Beck scraping the strings of the guitar for a purely percussive effect; it became a Top 20 hit in the United States in early 1966. Beck's guitar pyrotechnics came to fruition with "Shapes of Things," which (along with the Byrds' "Eight Miles High") can justifiably be classified as the first psychedelic rock classic. The group had already moved into social comment with a superb album track, "Mr. You're a Better Man than I"; on "Shapes of Things" they did so more succinctly, with Beck's explosively warped solo and feedback propelling the single near the U.S. Top Ten. At this point the group were as innovative as any in rock & roll, building their résumé with the similar hit follow-up to "Shapes of Things," "Over Under Sideways Down."

But the Yardbirds could not claim to be nearly as consistent as peers like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Kinks. 1966's Roger the Engineer was their first (and, in fact, only) studio album comprised entirely of original material, and highlighted the group's erratic quality, bouncing between derivative blues rockers and numbers incorporating monks-of-doom chants, Oriental dance rhythms, and good old guitar raveups, sometimes in the same track. Its highlights, however, were truly thrilling; even when the experiments weren't wholly successful, they served as proof that the band was second to none in their appetite for taking risks previously unheard of within rock.

Yet at the same time, the group's cohesiveness began to unravel when bassist Samwell-Smith -- who had shouldered most of the production responsibilities as well -- left the band in mid-1966. Jimmy Page, by this time fed up with session work, eagerly joined on bass. It quickly became apparent that Page had more to offer, and the group unexpectedly reorganized, Dreja switching from rhythm guitar to bass, and Page assuming dual lead guitar duties with Beck.

It was a dream lineup that was, like the best dreams, too good to be true, or at least to last long. Only one single was recorded with the Beck/Page lineup, "Happenings Ten Years Time Ago," which -- with its astral guitar leads, muffled explosions, eerie harmonies, and enigmatic lyrics -- was psychedelia at its pinnacle. But not at its most commercial; in comparison with previous Yardbirds singles, it fared poorly on the charts, reaching only number 30 in the States. Around this time, the group (Page and Beck in tow) made a memorable appearance in Michaelangelo Antonioni's film classic Blow Up, playing a reworked version of "The Train Kept-A-Rollin'" (retitled "Stroll On"). But in late 1966, Beck -- who had become increasingly unreliable, not turning up for some shows and suffering from nervous exhaustion -- left the band, emerging the following year as the leader of the Jeff Beck Group.

The remaining Yardbirds were determined to continue as a quartet, but in hindsight it was Beck's departure that began to burn out a band that had already survived the loss of a couple important original members. Also to blame was their mysterious failure to summon original material on the order of their classic 1965-1966 tracks. More to blame than anyone, however, was Mickey Most (Donovan, Herman's Hermits, Lulu, the Animals), who assumed the producer's chair in 1967, and matched the group with inappropriately lightweight pop tunes. The band's unbridled experimentalism would simmer in isolated moments on some b-sides and album tracks, like "Puzzles," the psychedelic U.F.O. instrumental "Glimpses," and the acoustic "White Summer," which would serve as a blueprint for Page's acoustic excursions with Led Zeppelin. "Little Games," "Ha Ha Said the Clown," and "Ten Little Indians" were all low-charting singles for the group in 1967, but were travesties compared to the magnificence of their previous hits, trading in fury and invention for sappy singalong pop. The 1967 Little Games album (issued in the U.S. only) was little better, suffering from both hasty, anemic production and weak material.

The Yardbirds continued to be an exciting concert act, concentrating most of their energies upon the United States, having been virtually left for dead in their native Britain. The b-side of their final single, the Page-penned "Think About It," was the best track of the entire Jimmy Page era, showing they were still capable of delivering intriguing, energetic psychedelia. It was too little too late; the group was truly on the wane by 1968, as an artistic rift developed within the ranks. To over-generalize somewhat, Relf and McCarty wanted to pursue more acoustic, melodic music; Page especially wanted to rock hard and loud. A live album was recorded in New York in early 1968, but scrapped; overdubbed with unbelievably cheesy crowd noises, it was briefly released in 1971 after Page had become a superstar in Led Zeppelin, but was withdrawn in a matter of days (it has since been heavily bootlegged). By this time the group was going through the motions, leaving Page holding the bag after a final show in mid-1968. Relf and McCarty formed the first incarnation of Renaissance. Page fulfilled existing contracts by assembling a "New Yardbirds" that, as many know, would soon change their name to Led Zeppelin.

It took years for the rock community to truly comprehend the Yardbirds' significance; younger listeners were led to the recordings in search of the roots of Clapton, Beck, and Page, each of whom had become a superstar by the end of the 1960s. Their wonderful catalog, however, has been subject to more exploitation than any other group of the '60s; dozens, if not hundreds, of cheesy packages of early material are generated throughout the world on a seemingly monthly basis. Fortunately, the best of the reissues cited below (on Rhino, Sony, Edsel and EMI) are packaged with great intelligence, enabling both collectors and new listeners to acquire all of their classic output with a minimum of fuss and repetition.

Thirty-five years after their break up in 1968, original members Chris Dreja and Jim McCarty pulled together a slew of new musicians to record a new album under the Yardbirds moniker, titled Birdland, and followed it with a tour of the United States.