| B i o g r a p h y |

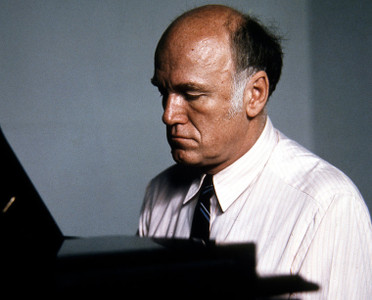

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter (Святослав Теофилович Рихтер

March 20, 1915 – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet pianist known for the

depth of his interpretations, virtuoso technique, and vast repertoire.

He is considered one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century.

Richter was born near Zhytomyr (Ukraine), in the Russian Empire. His

father, Teofil Danilovich Richter (1872–1941), was a German expatriate

pianist, organist, and composer who had studied in Vienna. His mother,

Anna Pavlovna (née Moskaleva; 1893–1963), was from a landowning family,

and at one point had been a pupil of her future husband. In 1918, when

Richter's parents were in Odessa, the Civil War separated them from

their son, and Richter moved in with his aunt Tamara. He lived with her

from 1918 to 1921, and it was then that his interest in art first

manifested itself: he first became interested in painting, which his

aunt taught him.

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter (Святослав Теофилович Рихтер

March 20, 1915 – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet pianist known for the

depth of his interpretations, virtuoso technique, and vast repertoire.

He is considered one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century.

Richter was born near Zhytomyr (Ukraine), in the Russian Empire. His

father, Teofil Danilovich Richter (1872–1941), was a German expatriate

pianist, organist, and composer who had studied in Vienna. His mother,

Anna Pavlovna (née Moskaleva; 1893–1963), was from a landowning family,

and at one point had been a pupil of her future husband. In 1918, when

Richter's parents were in Odessa, the Civil War separated them from

their son, and Richter moved in with his aunt Tamara. He lived with her

from 1918 to 1921, and it was then that his interest in art first

manifested itself: he first became interested in painting, which his

aunt taught him.

In 1921 the family was reunited, and the Richters moved to Odessa, where

Teofil taught at the Odessa Conservatory and, briefly, worked as

organist of a Lutheran church. In early 1920s Richter became interested

in music (as well as other art forms such as cinema, literature, and

theatre) and started studying piano. Unusually, he was largely

self-taught. His father only gave him a basic education in music, and so

did one of his father's pupils, a Czech harpist.

Even at an early age, Richter was an excellent sight-reader and

regularly practised with local opera and ballet companies. He developed a

lifelong passion for opera, vocal and chamber music that found its full

expression in the festivals he established in Grange de Meslay, France,

and in Moscow, at the Pushkin Museum. At age 15, he started to work at

the Odessa Opera, where he accompanied the rehearsals.

On March 19, 1934, Richter gave his first recital, at the Engineers'

Club of Odessa; but he did not formally start studying piano until three

years later, when he decided to seek out Heinrich Neuhaus, a famous

pianist and piano teacher, at the Moscow Conservatory. During Richter's

audition for Neuhaus (at which he performed Chopin's Ballade No. 4),

Neuhaus apparently whispered to a fellow student, "This man's a genius".

Although Neuhaus taught many great pianists, including Emil Gilels and

Radu Lupu, it is said that he considered Richter to be "the genius

pupil, for whom he had been waiting all his life," while acknowledging

that he taught Richter "almost nothing."

Early in his career, Richter also tried his hand at composing, and it

even appears that he played some of his compositions during his audition

for Neuhaus. He gave up composition shortly after moving to Moscow.

Years later, Richter explained this decision as follows: "Perhaps the

best way I can put it is that I see no point in adding to all the bad

music in the world".

By the beginning of World War II, Richter's parents' marriage had failed

and his mother had fallen in love with another man. Because Richter's

father was a German, he was under suspicion by the authorities and a

plan was made for the family to flee the country. Due to her romantic

involvement, his mother did not want to leave and so they remained in

Odessa. In August 1941 his father was arrested and later found guilty of

espionage, being sentenced to death on 6 October 1941. Richter didn't

speak to his mother again until shortly before her death nearly 20 years

later in connection with his first US tour.

In 1945, Richter met and accompanied in recital the soprano Nina

Dorliak. Richter and Dorliak thereafter remained companions until his

death, although they never married. She accompanied Richter both in his

complex life and career. She supported him in his last sickness, and

died herself a few months later, on May 17, 1998.

It was very widely rumored that Richter was homosexual and that having a

female companion provided a social front for his sexual orientation,

because homosexuality was still widely seen as strongly taboo and could

result in legal repercussions. Richter had a tendency to be private and

withdrawn and was not open to interviews. He never publicly discussed

his personal life until in the last year of his life filmmaker Bruno

Monsaingeon convinced him to be interviewed for a documentary.

In 1949 Richter won the Stalin Prize, which led to extensive concert

tours in Russia, Eastern Europe and China. He gave his first concerts

outside the Soviet Union in Czechoslovakia in 1950. In 1952, Richter was

invited to play Franz Liszt in a film based on the life of Mikhail

Glinka, called Kompozitor Glinka (Russian: Композитор Глинка, "The

Composer Glinka"; a remake of the 1946 film Glinka). The title role was

played by Boris Smirnov.

On February 18, 1952, Richter made his debut as a conductor (a role he

never again assumed) when he led the world premiere of Prokofiev's

Symphony-Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E minor, with Mstislav

Rostropovich as the soloist.

In 1960, even though he had a reputation for being "indifferent" to

politics, Richter defied the authorities when he performed at Boris

Pasternak's funeral. (He had played Prokofiev's Violin Sonata No. 1 at

Joseph Stalin's funeral in 1953, with David Oistrakh.)

Having received the Stalin and Lenin prizes and become People's Artist

of the RSFSR, he gave his first tour concerts in the USA in 1960, and in

England and France in 1961.

The West first became aware of Richter through recordings made in the

1950s. One of Richter's first advocates in the West was Emil Gilels, who

stated during his first tour of the United States that the critics (who

were giving Gilels rave reviews) should "wait until you hear Richter."

Richter's first concerts in the West took place in May 1960, when he was

allowed to play in Finland, and on October 15, 1960, in Chicago, where

he played Brahms's Second Piano Concerto accompanied by the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra and Erich Leinsdorf, creating a sensation. In a

review, noted Chicago Tribune music critic Claudia Cassidy, who was

known for her unkind reviews of established artists, recalled Richter

first walking on stage hesitantly, looking vulnerable (as if about to be

"devoured"), but then sitting at the piano and dispatching "the

performance of a lifetime". Richter's 1960 tour of the United States

culminated in a series of concerts at Carnegie Hall.

Richter disliked performing in the United States and the high

expectations of American audiences. Following a 1970 incident at Alice

Tully Hall in New York City, when Richter's performance alongside David

Oistrakh was disrupted by anti-Soviet protests, Richter vowed never to

return. Rumors of a planned return to Carnegie Hall surfaced in the last

years of Richter's life, although it is not clear if there was any

truth behind them.

In 1961, Richter played for the first time in London. His first recital,

pairing works of Haydn and Prokofiev, was received with hostility by

British critics. Notably, Neville Cardus concluded that Richter's

playing was "provincial", and wondered why Richter had been invited to

play in London, given that London had plenty of "second class" pianists

of its own. Following a July 18, 1961, concert, where Richter performed

both of Liszt's piano concertos, the critics reversed course.

In 1963, after searching in the Loire Valley, France, for a venue

suitable for a music festival, Richter discovered La Grange de Meslay

several kilometres north of Tours. The festival was established by

Richter and became an annual event.

In 1970, Richter visited Japan for the first time, traveling across

Siberia by railway and boat as he disliked flying. He played Beethoven,

Schumann, Mussorgsky, Prokofiev, Bartók and Rachmaninoff, as well as

works by Mozart and Beethoven with Japanese orchestras. He visited Japan

eight times.

Later years

While he very much enjoyed performing for an audience, Richter hated

planning concerts years in advance, and in later life took to playing at

very short notice in small, most often darkened halls, with only a

small lamp lighting the score. Richter said that this setting helped the

audience focus on the music being performed, rather than on extraneous

and irrelevant matters such as the performer's grimaces and gestures.