| B i o g r a p h y |

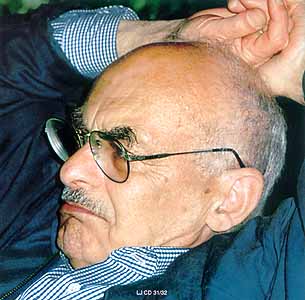

Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava (also transliterated as Boulat Okudjava/Okoudjava/Okoudzhava; Russian: Булат Шалвович Окуджава,

Georgian: ბულატ ოკუჯავა) (May 9, 1924 – June 12, 1997) was one of

the founders of the Russian genre called "author's song" (авторская

песня, avtorskaya pesnya). He was of Georgian origin, born in Moscow

and died in Paris. He was the author of about 200 songs, set to his own

poetry. His songs are a mixture of Russian poetic and folksong

traditions and the French chansonnier style represented by such

contemporaries of Okudzhava as Georges Brassens. Though his songs were

never overtly political (in contrast to those of some of his fellow

"bards"), the freshness and independence of Okudzhava's artistic voice

presented a subtle challenge to Soviet cultural authorities, who were

thus hesitant for many years to give official sanction to Okudzhava as

a singer-songwriter.

Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava (also transliterated as Boulat Okudjava/Okoudjava/Okoudzhava; Russian: Булат Шалвович Окуджава,

Georgian: ბულატ ოკუჯავა) (May 9, 1924 – June 12, 1997) was one of

the founders of the Russian genre called "author's song" (авторская

песня, avtorskaya pesnya). He was of Georgian origin, born in Moscow

and died in Paris. He was the author of about 200 songs, set to his own

poetry. His songs are a mixture of Russian poetic and folksong

traditions and the French chansonnier style represented by such

contemporaries of Okudzhava as Georges Brassens. Though his songs were

never overtly political (in contrast to those of some of his fellow

"bards"), the freshness and independence of Okudzhava's artistic voice

presented a subtle challenge to Soviet cultural authorities, who were

thus hesitant for many years to give official sanction to Okudzhava as

a singer-songwriter.

Bulat Okudzhava was born in Moscow on 9 May 1924 into a family of communists who had come from Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, for study and work connected with the Communist Party. The son of a Georgian father and an Armenian mother, Bulat Okudzhava spoke and wrote only in Russian. This was because his mother, who spoke Georgian, Azeri, and, of course, Armenian, had always requested that everyone who came to visit her house "Please, speak the language of Lenin - Russian." His father, a high Communist Party member from Georgia, was arrested in 1937 during the Great Purge and executed as a German spy on the basis of a false accusation. His mother was also arrested and spent 18 years in the prison camps of the Gulag (1937-1955). Bulat Okudzhava returned to Tbilisi and lived there with relatives.

In 1941, at the age of 17, one year before his scheduled school graduation, he volunteered for the Red Army infantry and from 1942 participated in the war with Nazi Germany. With the end of the Second World War, after his discharge from the service in 1945, he returned to Tbilisi where he passed his high school graduation tests and enrolled in Tbilisi State University, graduating in 1950. After graduating, he worked as a teacher - first in a rural school in the village of Shamordino in Kaluga district, and later in the city of Kaluga itself.

In 1956, three years after the death of Stalin, Okudzhava returned to Moscow, where he worked first as an editor in the publishing house Molodaya Gvardiya ("Young Guard"), and later as the head of the poetry division at the most prominent national literary weekly in the former USSR, Literaturnaya Gazeta ("Literary Gazette"). It was then, in the middle of the 1950s, that he began to compose songs and to perform them, accompanying himself on a Russian guitar.

Soon he was giving concerts. He only employed a few chords and had no formal training in music, but he possessed an exceptional melodic gift, and the intelligent lyrics of his songs blended perfectly with his music and his voice. His songs were praised by his friends, and amateur recordings were made. These unofficial recordings were widely copied (as so-called magnitizdat) and spread across the country (and in Poland), where other young people picked up guitars and started singing the songs for themselves. In 1969, his lyrics appeared in the classic Soviet film White Sun of the Desert.

Though Okudzhava's songs were not published by any official media organization until the late 1970s, they quickly achieved enormous popularity (especially among the intelligentsia) - mainly in the USSR at first, but soon among Russian-speakers in other countries as well. Vladimir Nabokov, for example, cited his Sentimental March in the novel Ada or Ardor.

Okudzhava, however, regarded himself primarily as a poet and claimed that his musical recordings were insignificant. During the 1980s, he also published a great deal of prose (his novel The Show is Over won him the Russian Booker Prize in 1994). By the 1980s, recordings of Okudzhava performing his songs finally began to be officially released in the Soviet Union, and many volumes of his poetry appeared separately. In 1991, he was awarded the USSR State Prize.

Okudzhava died in Paris on 12 June 1997, and is buried in the Vagankovo Cemetery in Moscow. A monument marks the building at 43 Arbat Street where he lived. His dacha in Peredelkino is open to the public as a museum.

Okudzhava, as most bards, did not come from a musical background. He learned basic guitar skills with the help of some friends. He also knew how to play basic chords on a piano.

Okudzhava tuned his Russian guitar in the special "Russian tuning" of D'-G'-C-D-g-b-d' (thickest to thinnest string), and often lowering it by one or two tones down to better accommodate his voice. He played in a classical manner, usually finger picking the strings in an ascending/descending arpeggio or waltz pattern, with an alternating bass picked by the thumb.

Initially Okudzhava was taught three basic chord shapes, towards the end of his life he claimed to know a total seven.

Many of Okudzhava's songs are in the key of C minor (with downtuning B flat or A minor), centering around the C minor shape (X00X011, thickest to thinnest string), then progressing to a D 7 (00X0433), then either an E flat minor (X55X566) or C major (55X5555). In addition to the aforementioned shapes, the E flat major chord (X55X567) was often featured for songs in a major key, usually C major (with downtuning B flat or A major).

By the nineties, Okudzhava adopted the increasingly more popular six string guitar but retained the Russian tuning, subtracting the fourth string which was convenient to his style of playing.

"The composers hated me. The singers detested me. The guitarists were terrified by me."

Bulat Okudzhava