| B i o g r a p h y |

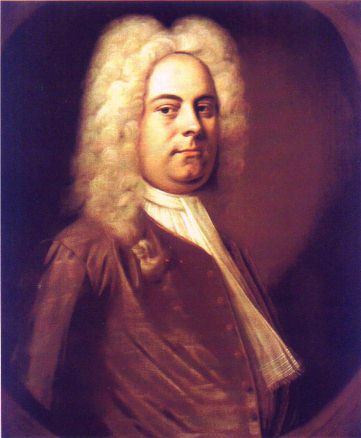

Georg Fridric Händel was born in Halle (Germany), 23 February 1685 and died London, 14 April 1759.

Georg Fridric Händel was born in Halle (Germany), 23 February 1685 and died London, 14 April 1759.

He was born Georg Friederich Händel, son of a barber-surgeon

who intended him for the law. At first he practised music

clandestinely, but his father was encouraged to allow him to study and

he became a pupil of Zachow, the principal organist in Halle. When he

was 17 he was appointed organist of the Calvinist Cathedral, but a year

later he left for Hamburg. There he played the violin and harpsichord

in the opera house, where his Almira was given at the beginning of

1705, soon followed by his Nero. The next year he accepted an

invitation to Italy, where he spent more than three years, in Florence,

Rome, Naples and Venice. He had operas or other dramatic works given in

all these cities (oratorios in Rome, including La resurrezione) and,

writing many Italian cantatas, perfected his technique in setting

Italian words for the human voice. In Rome he also composed some Latin

church music.

He left Italy early in 1710 and went to Hanover, where he was

appointed Kapellmeister to the elector. But he at once took leave to

take up an invitation to London, where his opera Rinaldo was produced

early in 1711. Back in Hanover, he applied for a second leave and

returned to London in autumn 1712. Four more operas followed in

1712-15, with mixed success; he also wrote music for the church and for

court and was awarded a royal pension. In 1716 he may have visited

Germany (where possibly he set Brockes's Passion text); it was probably

the next year that he wrote the Water Music to serenade George I at a

river-party on the Thames. In 1717 he entered the service of the Earl

of Carnarvon (soon to be Duke of Chandos) at Edgware, near London,

where he wrote 11 anthems and two dramatic works, the evergreen Acis

and Galatea and Esther, for the modest band of singers and players

retained there.

In 1718-19 a group of noblemen tried to put Italian opera in London

on a firmer footing, and launched a company with royal patronage, the

Royal Academy of Music; Handel, appointed musical director, went to

Germany, visiting Dresden and poaching several singers for the Academy,

which opened in April 1720. Handel's Radamisto was the second opera and

it inaugurated a noble series over the ensuing years including Ottone,

Giulio Cesare, Rodelinda, Tamerlano and Admeto. Works by Bononcini

(seen by some as a rival to Handel) and others were given too, with

success at least equal to Handel's, by a company with some of the

finest singers in Europe, notably the castrato Senesino and the soprano

Cuzzoni. But public support was variable and the financial basis

insecure, and in 1728 the venture collapsed. The previous year Handel,

who had been appointed a composer to the Chapel Royal in 1723, had

composed four anthems for the coronation of George II and had taken

British naturalization.

Opera remained his central interest, and with the Academy

impresario, Heidegger, he hired the King's Theatre and (after a journey

to Italy and Germany to engage fresh singers) embarked on a five-year

series of seasons starting in late 1729. Success was mixed. In 1732

Esther was given at a London musical society by friends of Handel's,

then by a rival group in public; Handel prepared to put it on at the

King's Theatre, but the Bishop of London banned a stage version of a

biblical work. He then put on Acis, also in response to a rival

venture. The next summer he was invited to Oxford and wrote an

oratorio, Athalia, for performance at the Sheldonian Theatre.

Meanwhile, a second opera company ('Opera of the Nobility', including

Senesino) had been set up in competition with Handel's and the two

competed for audiences over the next four seasons before both failed.

This period drew from Handel, however, such operas as Orlando and two

with ballet, Ariodante and Alcina, among his finest scores.

During the rest of the 1730s Handel moved between Italian opera and

the English forms, oratorio, ode and the like, unsure of his future

commercially and artistically. After a joumey to Dublin in 1741-2,

where Messiah had its premiere (in aid of charities), he put opera

behind him and for most of the remainder of his life gave oratorio

performances, mostly at the new Covent Garden theatre, usually at or

close to the Lent season. The Old Testament provided the basis for most

of them (Samson, Belshazar, Joseph. Joshua, Solomon, for example), but

he sometimes experimented, turning to classical mythology (Semele,

Hercules) or Christian history (Theodora), with little public success.

All these works, along with such earlier ones as Acis and his two

Cecilian odes (to Dryden words), were performed in concert form in

English. At these performances he usually played in the interval a

concerto on the organ (a newly invented musical genre) or directed a

concerto grosso (his op.6, a set of 12, published in 1740, represents

his finest achievement in the form).

During his last decade he gave regular performances of Messiah,

usually with about 16 singers and an orchestra of about 40, in aid of

the Foundling Hospital. In 1749 he wrote a suite for wind instruments

(with optional strings) for performance in Green Park to accompany the

Royal Fireworks celebrating the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. His last

oratorio, composed as he grew blind, was Jephtha (1752); The Triumph of

Time and Truth (1757) is largely composed of earlier material. Handel

was very economical in the re-use of his ideas; at many times in his

life he also drew heavily on the music of others (though generally

avoiding detection) - such 'borrowings' may be of anything from a brief

motif to entire movements, sometimes as they stood but more often

accommodated to his own style.

Handel died in 1759 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, recognized

in England and by many in Germany as the greatest composer of his day.

The wide range of expression at his command is shown not only in the

operas, with their rich and varied arias, but also in the form he

created, the English oratorio, where it is applied to the fates of

nations as well as individuals. He had a vivid sense of drama. But

above all he had a resource and originality of invention, to be seen in

the extraordinary variety of music in the op.6 concertos, for example,

in which melodic beauty, boldness and humour all play a part, that

place him and J.S. Bach as the supreme masters of the Baroque era in

music.

The Grove Concise Dictionary of Music