|

..:: audio-music dot

info ::..

|

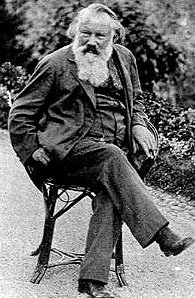

Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897)

Born: May 7, 1833 in Hamburg,

Germany

Died: April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria

Johannes Brahms

felt that

Schubert was the last composer to be born at a truly propitious time.

Brahms' artistic credo was expressed by his famous statement that, "If

we can not compose as beautifully as Mozart and Haydn, let us at least

try to compose as purely." It is perhaps the conviction that he had

come too late to be truly on on a level with those he most admired and

understood that gave his music its deep, reflective melancholy.

Autumnal is the adjective often given to Brahms' output and it applies

even to much of the music of his youth.

In many respects Brahms brings the classical-romantic continuum to an

end. He felt no kinship to the "music of the future" that was the

mantle of Wagner and Liszt, and throughout his life, Brahms was one of

the few composers of his era interested in the classical approach to

variations, sonatas, and such 18th century contrapuntal procedures as

fugue and passacaglia. In the age of the bravura concerto, where the

solo instrument is often merely accompanied by the orchestra, Brahms,

in his Violin Concerto and two piano concertos, wrote in a truly

classical manner that treats soloist and orchestra as symbiotic equals

in the tradition of Mozart and Beethoven. His late Double Concerto even

recalls some Baroque procedures.

Like Bach - another great conservative - Brahms sums up what went

before him thereby synthesizing the romantic harmony and language of

Schubert, Schumann, and Mendelssohn with classical forms and the

counterpoint of the Baroque. But this is not to say that Brahms was not

at the same time truly of his own era. In fact, Arnold Schoenberg wrote

an important essay stressing the forward and radical implications of

Brahms' harmony. The first Intermezzo of op. 119 is an example of this

with its complex chord structures that verge on the polytonal.

Brahms was born in Hamburg, the son of a double bass player. He

received an early grounding in the classics - especially Bach - from

his teacher, Eduard Marxsen, who was the dedicatee of his second piano

concerto. Another formative aspect of his youth was playing in dives

and bordellos in order to bring in extra money for the family. Brahms

later acknowledged that this early contact with the opposite sex from

such a strange vantage point contributed to his ultimately remaining a

lifelong bachelor.

The great love of his life was what was most probably a platonic

friendship with Clara Schumann, although there have certainly been

speculations to the contrary. Brahms became close to the Schumanns when

Robert championed his work, and Brahms consoled Clara during the

anguish of Robert's disease. A lasting love ultimately developed for

the great artist who was fourteen years her junior. Although their

complex relationship had its difficulties, especially when Brahms at

one point developed an interest in one of Clara's daughters, they

stayed lifelong friends and it was often Clara to whom the tremendously

self critical Brahms first sent his works.

Brahms was intensely aware of the weight of the tradition he was trying

to uphold. It is estimated the chamber music we have is only one

quarter of what he actually wrote. He ruthlessly destroyed anything

that he considered unworthy, and thus, we have nothing comparable to

Beethoven's sketch books to understand him by. He was certainly a slow

and meticulous worker and did not complete his First Symphony until he

was forty-three and after eleven years of work, not to mention two

orchestral serenades and the First Piano Concerto in preparation for

the act. "You have no idea what it is to hear the tromp of a genius

over your shoulder," he said referring to the daunting legacy of

Beethoven's symphonies. When the similarity of the great last movement

theme to Beethoven's Ninth was pointed out, Brahms response was, "any

fool can see that."

Brahms was famously brusque and prickly on the surface, although

friends knew this was to guard a very sensitive and vulnerable soul.

This might be said to describe the music itself. Much of the power and

attraction of Brahms' music is the great warmth and generosity of a

romantic spirit held in check by the most rigorous intellect. If Brahms

wears his heart on his sleeve, it is only after he has painstakingly

knitted the sweater from the purest wool. While there are many

examples, one that comes to mind is the second String Sextet in G, op.

36. After the mysterious opening and tonally ambiguous first theme

group, the second theme comes pouring forth without inhibition and a

directness that goes straight to one's heart. An opposite example might

be the Bb Piano Concerto, where the warmly noble ascending b flat, c, d

of the opening theme is brusquely contradicted by the same notes

descending in reverse in the bass at the beginning of the subsequent

scherzo in D minor.

After the tremendous effort of completing the First Symphony, the

sunnier Second followed relatively easily. It is almost as if Brahms'

labor pains on one piece were sufficient to give birth to two. Thus we

have the two piano quartets, op. 25 and 26, the two string quartets of

op. 51 and the two late clarinet sonatas, op. 120. For all this

instrumental music, it is sometimes forgotten that a great deal of

Brahms' output was vocal music ranging from wonderful lieder in

tradition of Schubert and Schumann to large choral works such as the

Requiem, op. 43, inspired by his mother's death, and the work that

first made him truly famous.

As Brahms got older his work tended to become more concise; the C minor

piano quartet, op. 60, is much more terse than the expansive earlier

quartets or the culminating work of his first period, the F minor Piano

Quintet, op. 34. He went into a premature retirement after his op. 111

String Quintet in 1890 that was luckily brought to an end by the

inspiration of hearing clarinettist Richard Mulfeld. The two clarinet

sonatas were followed by the B minor Clarinet Quintet, op. 115, perhaps

his greatest chamber piece. The last opuses are mainly keyboard works,

primarily the sets of intimate Intermezzi ( 3 Intermezzi, op. 117;

Intermezzo, op. 118, No. 2; Intermezzi, op. 119: No. 1 in B; No. 2 in E

) and other Klavierstucke, op. 116-119. In these works one hears the

deep last reflections of a century and an era.

Copyright ©

Classical Archives, LLC. All rights reserved.

Die

Bratschensonaten · F.A.E.-Sonate · Scherzo

(Deutsche Grammophone, 1975)

Klavierkonzert

Nr.

1 - Vier Balladen op. 10 (Decca Classics, 1976)

The Four Symphonies (Virtuoso

Records, 1989)

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No.1 and No.2, Piano Concerto No.2 (Grammofono 2000, 1997)

The Four Symphonies (Testament

Records, 2000)

Brahms & Dvorák & Borodin & Smetana:

Tänze

(Deutsche Grammophone, 1972)

Brahms

& Kabalevsky:

Piano

Concerto No. 2 / Piano Sonata No. 2 (Cedar, 1998)

Brahms

& Schumann:

Piano Concerto No. 2 / Piano Sonata No.2 (EMI Classics, 1993)

Felix Mendelssohn

& Johannes Brahms:

Violinkonzerte

(Deutsche Grammophone, 1982)

Born: May 7, 1833 in Hamburg,

Germany

Born: May 7, 1833 in Hamburg,

Germany