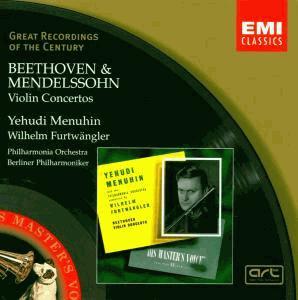

| Artist: | Ludwig van Beethoven |

| Title: | Violin Concertos |

| Released: | 1954 |

| Label: | EMI Classics |

| Time: | 71:31 |

| Producer(s): | |

| Appears with: | |

| Category: | Classic |

| Rating: | *********. (9/10) |

| Media type: | CD |

| Purchase date: | 2001.01.06 |

| Price in €: | 8,58 |

| Web address: | www.emiclassics.com |