..:: audio-music dot info ::.. |

| A l b u m D e t a i l s |

|

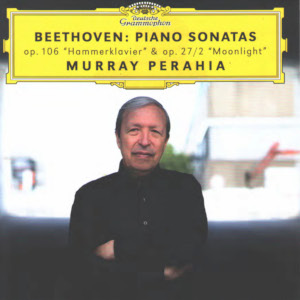

Label: | Deutsche Grammophon |

| Released: | 2018.02.09 | |

| Time: |

55:52 |

|

| Category: | Classical | |

| Producer(s): | Andreas Neubronner | |

| Rating: | ||

| Media type: | CD |

|

| Web address: | www.deutschegrammophon.com | |

| Appears with: | ||

| Purchase date: | 2018 | |

| Price in €: | 1,00 | |

| S o n g s , T r a c k s |

| A r t i s t s , P e r s o n n e l |

| C o m m e n t s , N o t e s |

| L y r i c s |

| M P 3 S a m p l e s |