|

..:: audio-music dot

info ::..

|

Tomaso Albinoni, Arcangelo Corelli, Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Christoph Pachelbel, Francesco Onofrio Manfredini

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni

was born in Venice in 1671, eldest son of a wealthy paper merchant. At

an early age he became proficient as a singer and, more notably, as a

violinist, though not being a member of the performers' guild he was

unable to play publicly so he turned his hand to composition. His first

opera, Zenobia, regina de Palmireni, was produced in Venice in 1694,

coinciding with his first collection of instrumental music, the 12

Sonate a tre, Op.1. Thereafter he divided his attention almost equally

between vocal composition (operas, serenatas and cantatas) and

instrumental composition (sonatas and concertos).

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni

was born in Venice in 1671, eldest son of a wealthy paper merchant. At

an early age he became proficient as a singer and, more notably, as a

violinist, though not being a member of the performers' guild he was

unable to play publicly so he turned his hand to composition. His first

opera, Zenobia, regina de Palmireni, was produced in Venice in 1694,

coinciding with his first collection of instrumental music, the 12

Sonate a tre, Op.1. Thereafter he divided his attention almost equally

between vocal composition (operas, serenatas and cantatas) and

instrumental composition (sonatas and concertos).

Until his father's death in 1709, he was able to cultivate music more

for pleasure than for profit, referring to himself as "Dilettante

Veneto" - a term which in 18th century Italy was totally devoid of

unfavorable connotations. Under the terms of his father's will he was

relieved of the duty (which he would normally have assumed as eldest

son) to take charge of the family business, this task being given to

his younger brothers. Henceforth he was to be a full-time musician, a

prolific composer who according to one report, also ran a successful

academy of singing.

A lifelong resident of Venice, Albnoni married an opera singer,

Margherita Raimondi (d 1721), and composed as many as 81 operas several

of which were performed in northern Europe from the 1720s onwards. In

1722 he traveled to Munich at the invitation of the Elector of Bavaria

to supervise performances of I veri amici and Il trionfo d'amore as

part of the wedding celebrations for the Prince-Elector and the

daughter of the late Emperor Joseph I.

Most of his operatic works have been lost, having not been published

during his lifetime. Nine collections of instrumental works were

however published, meeting with considerable success and consequent

reprints; thus it is as a composer of instrumental music (99 sonatas,

59 concertos and 9 sinfonias) that he is known today. In his lifetime

these works were favorably compared with those of Corelli and Vivaldi,

and his nine collections published in Italy, Amsterdam and London were

either dedicated to or sponsored by an impressive list of southern

European nobility.

Albinoni was particularly fond of the oboe, a relatively new

introduction in Italy, and is credited with being the first Italian to

compose oboe concertos (Op. 7, 1715). Prior to Op.7, Albinoni had not

published any compositions with parts for wind instruments.

The concerto, in particular, had been regarded as the province of

stringed instruments. It is likely that the first concertos featuring a

solo oboe appeared from German composers such as Telemann or Handel.

Nevertheless, the four concertos with one oboe (Nos. 3, 6, 9 and 12)

and the four with two oboes (Nos. 2, 5, 8 and 11) in Albinoni's Op.7

were the first of their kind to be published, and proved so successful

that the composer repeated the formula in Op.9 (1722).

The Italian

composer and violinist Arcangelo

Corelli

exercised a wide influence on his contemporaries and on the succeeding

generation of composers. Born in Fusignano, Italy, in 1653, a full

generation before Bach or Handel, he studied in Bologna, a

distinguished musical center, then established himself in Rome in the

1670s. By 1679 had entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden,

who had taken up residence in Rome in 1655, after her abdication the

year before, and had established there an academy of literati that

later became the Arcadian Academy. Thanks to his musical achievements

and growing international reputation he found no trouble in obtaining

the support of a succession of influential patrons. History has

remembered him with such titles as "Founder of Modern Violin

Technique," the "World's First Great Violinist," and the "Father of the

Concerto Grosso."

The Italian

composer and violinist Arcangelo

Corelli

exercised a wide influence on his contemporaries and on the succeeding

generation of composers. Born in Fusignano, Italy, in 1653, a full

generation before Bach or Handel, he studied in Bologna, a

distinguished musical center, then established himself in Rome in the

1670s. By 1679 had entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden,

who had taken up residence in Rome in 1655, after her abdication the

year before, and had established there an academy of literati that

later became the Arcadian Academy. Thanks to his musical achievements

and growing international reputation he found no trouble in obtaining

the support of a succession of influential patrons. History has

remembered him with such titles as "Founder of Modern Violin

Technique," the "World's First Great Violinist," and the "Father of the

Concerto Grosso."

His contributions can be divided three ways, as violinist, composer,

and teacher. It was his skill on the new instrument known as the violin

and his extensive and very popular concert tours throughout Europe

which did most to give that instrument its prominent place in music. It

is probably correct to say that Corelli's popularity as a violinist was

as great in his time as was Paganini's during the 19th century. Yet

Corelli was not a virtuoso in the contemporary sense, for a beautiful

singing tone alone distinguished great violinists in that day, and

Corelli's tone quality was the most remarkable in all Europe according

to reports. In addition, Corelli was the first person to organize the

basic elements of violin technique.

Corelli's popularity as a violinist was equaled by his acclaim as a

composer. His music was performed and honored throughout all Europe; in

fact, his was the most popular instrumental music. It is important to

note in this regard that a visit of respect to the great Corelli was an

important part of the Italian tour of the young Handel. Yet Corelli's

compositional output was rather small. All of his creations are

included in six opus numbers, most of them being devoted to serious and

popular sonatas and trio sonatas. In the Sonatas Opus 5 is found the

famous "La Folia" Variations for violin and accompaniment. One of

Corelli's famous students, Geminiani, thought so much of the Opus 5

Sonatas that he arranged all the works in that group as Concerti

Grossi. However, it is in his own Concerti Grossi Opus 6 that Corelli

reached his creative peak and climaxed all his musical contributions.

Although Corelli was not the inventor of the Concerto Grosso principle,

it was he who proved the potentialities of the form, popularized it,

and wrote the first great music for it. Through his efforts, it

achieved the same pre-eminent place in the baroque period of musical

history that the symphony did in the classical period. Without

Corelli's successful models, it would have been impossible for Vivaldi,

Handel, and Bach to have given us their Concerto Grosso masterpieces.

The Concerto Grosso form is built on the principle of contrasting two

differently sized instrumental groups. In Corelli's, the smaller group

consists of two violins and a cello, and the larger of a string

orchestra. Dynamic markings in all the music of this period were based

on the terrace principle; crescendo and diminuendi are unknown,

contrasts between forte and piano and between the large and small

string groups constituting the dynamic variety of the scores.

Of all his compositions it was upon his Opus 6 that Corelli labored

most diligently and devotedly. Even though he wouldn't allow them to be

published during his lifetime, they still became some of the most

famous music of the time. The date of composition is not certain, for

Corelli spent many years of his life writing and rewriting this music,

beginning while still in his twenties.

The Trio Sonata, an instrumental composition generally demanding the

services of four players reading from three part-books, assumed

enormous importance in baroque music, developing from its earlier

beginnings at the start of the seventeenth century to a late flowering

in the work of Handel, Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach and their

contemporaries, alter the earlier achievements of Arcangelo Corelli in

the form. Instrumentation of the trio sonata, possibly for commercial

reasons, allowed some freedom of choice. Nevertheless the most

frequently found arrangement became that for two violins and cello,

with a harpsichord or other chordal instrument to fill out the harmony.

The trio sonata was the foundation of the concerto grosso, the

instrumental concerto that contrasted a concertino group of the four

instruments of the trio sonata with the full string orchestra, which

might double louder passages.

Corelli's dedications of his Sonatas mark his progress among the great

patrons of Rome. He dedicated his first set of twelve Church Sonatas,

Opus 1, published in 1681, to Queen Christina, describing the work as

the first fruits of his studies. His second set of trio Sonatas,

Chamber Sonatas, Opus 2, was published in 1685 with a dedication to a

new patron, Cardinal Pamphili, whose service he entered in 1687, with

the violinist Fornari and cellist Lulier. A third set of trio sonatas,

a second group of twelve Church Sonatas, Opus 3, was issued in 1689,

with a dedication to Francesco II of Modena, and a final set of a dozen

Chamber Sonatas, Opus 4, was published in 1694 with a dedication to a

new patron, Cardinal Ottoboni, the young nephew of Pope Alexander VIII,

after Cardinal Pamphili's removal in 1690 to Bologna. Cardinal Ottoboni

became Corelli's main patron, who made it possible for Corelli to

pursue his career without monetary worries, and it would seem that no

composer has ever had a more devoted or understanding patron.

Corelli's achievements as a teacher were again outstanding. Among his

many students were included not only Geminiani but the famed Antonio

Vivaldi. It was Vivaldi who became Corelli's successor as a composer of

the great Concerti Grossi and who greatly influenced the music of Bach.

Corelli occupied a leading position in the musical life of Rome for

some thirty years, performing as a violinist and directing performances

often on occasions of the greatest public importance. His style of

composition was much imitated and provided a model, both through a wide

dissemination of works published in his lifetime and through the

performance of these works in Rome. Corelli died a wealthy man on

January 19, 1713, at Rome in the 59th year of his life. But long before

his death, he had taken a place among the immortal musicians of all

time, and he maintains that exalted position today.

Antonio Vivaldi

was born in Venice on March 4th, 1678. Though ordained a priest in

1703, according to his own account, within a year of being ordained

Vivaldi no longer wished to celebrate mass because of physical

complaints ("tightness of the chest") which pointed to angina pectoris,

asthmatic bronchitis, or a nervous disorder. It is also possible that

Vivaldi was simulating illness - there is a story that he sometimes

left the altar in order to quickly jot down a musical idea in the

sacristy.... In any event he had become a priest against his own will,

perhaps because in his day training for the priesthood was often the

only possible way for a poor family to obtain free schooling.

Antonio Vivaldi

was born in Venice on March 4th, 1678. Though ordained a priest in

1703, according to his own account, within a year of being ordained

Vivaldi no longer wished to celebrate mass because of physical

complaints ("tightness of the chest") which pointed to angina pectoris,

asthmatic bronchitis, or a nervous disorder. It is also possible that

Vivaldi was simulating illness - there is a story that he sometimes

left the altar in order to quickly jot down a musical idea in the

sacristy.... In any event he had become a priest against his own will,

perhaps because in his day training for the priesthood was often the

only possible way for a poor family to obtain free schooling.

Though he wrote many fine and memorable concertos, such as the Four

Seasons and the Opus 3 for example, he also wrote many works which

sound like five-finger exercises for students. And this is precisely

what they were. Vivaldi was employed for most of his working life by

the Ospedale della Pietà. Often termed an "orphanage", this

Ospedale was in fact a home for the female offspring of noblemen and

their numerous dalliances with their mistresses. The Ospedale (see

illustration) was thus well endowed by the "anonymous" fathers; its

furnishings bordered on the opulent, the young ladies were well

looked-after, and the musical standards among the highest in Venice.

Many of Vivaldi's concerti were indeed exercises which he would play

with his many talented pupils.

Vivaldi's relationship with the Ospedale began right after his

ordination in 1703, when he was named as violin teacher there. Until

1709, Vivaldi's appointment was renewed every year and again after

1711. Between 1709 and 1711 Vivaldi was not attached to the Ospedale.

Perhaps in this period he was already working for the Teatro Sant'

Angelo, an opera theater. He also remained active as a composer - in

1711 twelve concertos he had written were published in Amsterdam by the

music publisher Estienne Roger under the title l'Estro armonico

(Harmonic Inspiration).

In 1713, Vivaldi was given a month's leave from the Ospedale della

Pietà in order to stage his first opera, Ottone in villa, in

Vicenza. In the 1713-4 season he was once again attached to the Teatro

Sant' Angelo, where he produced an opera by the composer Giovanni

Alberto Rostori (1692-1753).

As far as his theatrical activities were concerned, the end of 1716 was

a high point for Vivaldi. In November, he managed to have the Ospedale

della Pietà perform his first great oratorio, Juditha

Triumphans

devicta Holofernis barbaric. This work was an allegorical description

of the victory of the Venetians (the Christians) over the Turks (the

barbarians) in August 1716.

At the end of 1717 Vivaldi moved to Mantua for two years in order to

take up his post as Chamber Capellmeister at the court of Landgrave

Philips van Hessen-Darmstadt. His task there was to provide operas,

cantatas, and perhaps concert music, too. His opera Armida had already

been performed earlier in Mantua and in 1719 Teuzzone and Tito Manlio

followed. On the score of the latter are the words: "music by Vivaldi,

made in 5 days." Furthermore, in 1720 La Conduce o siano Li veri amici

was performed.

In 172O Vivaldi returned to Venice where he again staged new operas

written by himself in the Teatro Sant' Angelo. In Mantua he had made

the acquaintance of the singer Anna Giraud (or Giro), and she had moved

in to live with him. Vivaldi maintained that she was no more than a

housekeeper and good friend, just like Anna's sister, Paolina, who also

shared his house.

In his Memoires, the Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni gave the

following portrait of Vivaldi and Giraud: "This priest, an excellent

violinist but a mediocre composer, has trained Miss Giraud to be a

singer. She was young, born in Venice, but the daughter of a French

wigmaker. She was not beautiful, though she was elegant, small in

stature, with beautiful eyes and a fascinating mouth. She had a small

voice, but many languages in which to harangue." Vivaldi stayed

together with her until his death.

Vivaldi also wrote works on commission from foreign rulers, such as the

French king, Louis XV - the serenade La Sena festeggiante (Festival on

the Seine), for example. This work cannot be dated precisely, but it

was certainly written after 1720.

In Rome Vivaldi found a patron in the person of Cardinal Pietro

Ottoboni, a great music lover, who earlier had been the patron of

Arcangelo Corelli. And if we can believe Vivaldi himself, the Pope

asked him to come and play the violin for him at a private audience.

Earlier, in the 1660's, musical life in Rome had been enormously

stimulated by the presence of Christina of Sweden in the city. The

"Pallas of the North," as she was called, abdicated from the Swedish

throne in 1654. A few years later she moved to Rome and took up

residence in the Palazzo Riario. There she organized musical events

that were attended by composers such as Corelli and Scarlatti. Other

composers, too, such as Geminiani and Handel worked in Rome for periods

of time. Like them, Vivaldi profited from the favorable cultural

climate in the city.

Despite his stay in Rome and other cities, Vivaldi remained in the

service of the Ospedale della Pietà, which nominated him

"Maestro di concerti." He was required only to send two concertos per

month to Venice (transport costs were to the account of the client) for

which he received a ducat per concerto. His presence was never

required. He also remained director of the Teatro Sant' Angelo, as he

did in the 1726, 7 and 8 seasons.

Between 1725 and 1728 some eight operas were premiered in Venice and

Florence. Abbot Conti wrote of his contemporary, Vivaldi: "In less than

three months Vivaldi has composed three operas, two for Venice and a

third for Florence; the last has given something of a boost to the name

of the theater of that city and he has earned a great deal of money."

During these years Vivaldi was also extremely active in the field of

concertos. In 1725 the publication Il Cimento dell' Armenia e

dell'invenzione (The trial of harmony and invention), opus 8, appeared

in Amsterdam. This consisted of twelve concertos, seven of which were

descriptive: The Four Seasons, Storm at Sea, Pleasure and The Hunt.

Vivaldi transformed the tradition of descriptive music into a typically

Italian musical style with its unmistakable timbre in which the strings

play a major role.

These concertos were enormously successful, particularly in France. In

the second half of the 18th century there even appeared some remarkable

adaptations of the Spring concerto: Michel Corrette (1709-1795) based

his motet Laudate Dominum de coelis of 1765 on this concerto and, in

1775, Jean-Jacques Rousseau reworked it into a version for solo flute.

"Spring" was also a firm favorite of King Louis XV, who would order it

to be performed at the most unexpected moments, and Vivaldi received

various commissions for further compositions from the court at

Versailles.

In 1730 Vivaldi, his father, and Anna Giraud traveled to Prague. In

this music-loving city (half a century later Mozart would celebrate his

first operatic triumphs there) Vivaldi met a Venetian opera company

which between 1724 and 1734 staged some sixty operas in the theater of

Count Franz Anton von Sporck (for whom incidentally, Bach produced his

Four Shorter Masses). In the 1730-1731 season, two new operas by

Vivaldi were premiered there after the previous season had closed with

his opera Farnace, a work the composer often used as his showpiece.

At the end of 1731 Vivaldi returned to Venice, but at the beginning of

1732 he left again for Mantua and Verona. In Mantua, Vivaldi's opera

Semimmide was performed and in Verona, on the occasion of the opening

of the new Teatro Filarmonico, La fida Ninfa, with a libretto by the

Veronese poet and man of letters, Scipione Maffei, was staged.

After his stay in Prague, Vivaldi concentrated mainly on operas. No

further collections of instrumental music were published. However

Vivaldi continued to write instrumental music, although it was only to

sell the manuscripts to private persons or to the Ospedale della

Pietà, which after 1735 paid him a fixed honorarium of 100

ducats a year. In 1733 he met the English traveler, Edward Holdsworth,

who had been commissioned to purchase a few of Vivaldi's compositions

for the man of letters, Charles Jennens, author of texts for oratorios

by Handel. Holdsworth wrote to Jennens: "I spoke with your friend

Vivaldi today. He told me that he had decided to publish no more

concertos because otherwise he can no longer sell his handwritten

compositions. He earns more with these, he said, and since he charges

one guinea per piece, that must be true if he finds a goodly number of

buyers."

In 1738 Vivaldi was in Amsterdam where he conducted a festive opening

concert for the 100th Anniversary of the Schouwburg Theater. Returning

to Venice, which was at that time suffering a severe economic downturn,

he resigned from the Ospedale in 1740, planning to move to Vienna under

the patronage of his admirer Charles VI. His stay in Vienna was to be

shortlived however, for he died on July 28th 1741 "of internal fire"

(probably the asthmatic bronchitis from which he suffered all his life)

and, like Mozart fifty years later, received a modest burial. Anna

Giraud returned to Venice, where she died in 1750.

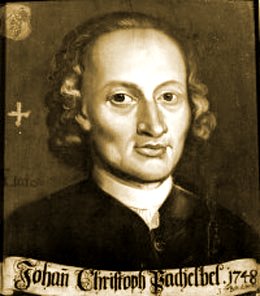

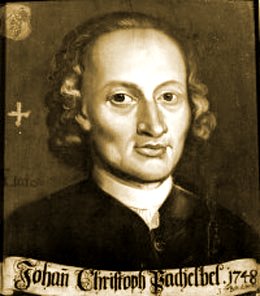

Johann Christoph Pachelbel

(1653 - 1706) German composer and organist. He studied music with

Heinrich Schwemmer and G. C. Wecker, attended lectures at the

Auditorium aegidianum and entered the university at Altdorf in 1669,

where he also served as organist at the Lorenzkirche. He was forced to

leave the university after less than a year owing to lack of funds, and

became a scholarship student at the Gymnasium poeticum at Regensburg,

taking private instruction under Kaspar Prentz. In 1673 Pachelbel went

to Vienna and became deputy organist at St. Stephen's Cathedral; in

1677 he became organist in Thuringen at the Eisenach court, where he

served for slightly over a year. . This was an important move, since it

was here that he became a dose friend of the town’s most

prominent musician, Johann Ambrosius Bach, the future father of Johann

Sebastian, and his family.

Johann Christoph Pachelbel

(1653 - 1706) German composer and organist. He studied music with

Heinrich Schwemmer and G. C. Wecker, attended lectures at the

Auditorium aegidianum and entered the university at Altdorf in 1669,

where he also served as organist at the Lorenzkirche. He was forced to

leave the university after less than a year owing to lack of funds, and

became a scholarship student at the Gymnasium poeticum at Regensburg,

taking private instruction under Kaspar Prentz. In 1673 Pachelbel went

to Vienna and became deputy organist at St. Stephen's Cathedral; in

1677 he became organist in Thuringen at the Eisenach court, where he

served for slightly over a year. . This was an important move, since it

was here that he became a dose friend of the town’s most

prominent musician, Johann Ambrosius Bach, the future father of Johann

Sebastian, and his family.

In 1678, Pachelbel obtained the first of the two important positions he

was to hold during his lifetime when he became organist at the

Protestant Predigerkirche at Erfurt, where he established his

reputation as organist, composer, and teacher. Erfurt was, of course,

the ancestral home of the Bach family, and there he met Ambrosius'

eldest son, Johann Christoph (the Ohrdruf Bach), whom he knew from

Eisenach and who lived in Erfurt from 1686 to 1689. Pachelbel undertook

the musical education of the young man who, not many years later, would

teach his brother Johann Sebastian all he knew when the latter came to

live with his family following the death of their parents.

Pachelbel started a family in Erfurt; after the early death of his

first wife and their child, he remarried and produced a highly artistic

household: of the couple's seven children, two would later become

organists, including his eldest son Wilhelm Hieronymus who acted as

Pachelbel's successor at Nuremberg for thirty-nine years, another son

who became an instrument maker and a daughter who achieved recognition

as a painter and engraver. Pachelbel left Erfurt some years later,

apparently looking for a better appointment, musician and organist for

the Wurttemberg court at Stuttgart (1690-92), and then in Gotha

(1692-95), where he was town organist. His travels finally led him home

when he was invited to succeed Wecker as organist of St. Sebald,

Nuremberg, after his former teacher's death in 1695; he obtained his

release from Gotha that same year and remained at St. Sebald until his

death. He died in the first months of 1706 at the young age of 52.

Johann Pachelbel was one of the dominant figures of late

seventeenth-century European keyboard music. An exact contemporary of

Georg Muffat he belonged to the generation that included German

composers Böhm, Bruhns and Fischer, French composers Raison,

Jullien and François Couperin, and the Englishman Purcell,

and

that came chronologically between Buxtehude and Bach.

The young Johann Sebastian Bach, at the time on his way back from

Lübeck, probably never met him. Perhaps it is because he was

already familiar with the work of Pachelbel, which was well-known

throughout central Germany, that he chose Buxtehude as his mentor. Many

of Pachelbel's students, in particular, had actively transmitted his

inimitable art of chorale variation, including Johann Christoph Bach

who doubtless passed the knowledge on to his younger brother. Another

important link in the chain is Johann Gottfried Walther, a contemporary

and cousin of Bach who was his colleague in Weimar. Walther was born in

Erfurt during Pachelbel's stay and studied with several students of the

master, and then in Nuremberg with Pachelbel's son, which made him a

worthy disciple of the master of St. Sebald. Walther also studied with

Werckmeister, a friend of Buxtehude, and played a pivotal role in the

transmission of the German organ repertoire to future generations,

which was effected mainly through oral tradition and manuscript copies

of unpublished works.

Pachelbel, like many of this foremost contemporaries, was somehow able

to combine his professional activities as a church musician, secular

musician and teacher, not to mention his responsibilities as the father

of a large family, with his activities as a composer. in keeping with

the customs of the time, he published only a small number of his

compositions, since copper engraving was an expensive process and

published works had to have some special feature to make them

attractive to prospective purchasers. First, in Erfurt, he brought out

a small collection of four chorales with variations in 1683, which he

entitled Musicaliscbe Sterbensgedancken (Musical Thoughts on Death;

next, in Nuremberg, six Sonatas for two violins and bass, and the

collection Musicalissche Eigötzung (Musical Rejoicing, circa

1691), eight chorale preludes, Acht Choräle zum Praeambulieren

in

1693, and lastly, in 1699, his master work, Hexachordum Apollinis, the

Hexachord of Apollo, containing six Arias with variations in six

different keys for harpsichord (or organ), including the famous Aria

Sebaldina in F minor, and which includes a dedication to Buxtehude and

his Vienna contemporary Ferdinand Tobias Richter.

Pachelbel's secular output consisted of around twenty harpsichord

suites, sets of variations and various instrumental works. As a parish

musician, though, the bulk of this work was written for church

services, in particular Mass and Vespers, in which both singers and

instrumentalists took part. Around twenty-six motets, nineteen

spiritual songs, thirteen Magnificats, spiritual concerts and masses

have survived. Like both Schütz and Buxtehude, Pachelbel liked

to

experiment with various instrumental configurations, from the smallest

—voice, two violins and continuo—to the most

grandiose. The

spiritual concert Lobet den Herrn in seinem Heiligtum (Praise the Lord

in his Sanctuary) is scored for five voices, two flutes, bassoon, five

trumpets, trombone, drums, cymbals, harp, two violins, three violas,

continuo and organ. However, it is Pachelbel's organ music that takes

pride of place in his production, since the surviving corpus is one of

the most extensive of the period: with some two hundred and fifty

separate pieces it is, numerically, twice the size of Buxtehude's, and

evidence of other lost works has been found.

Much of the organ music was intended for service use. It is important

to remember that Luther's religious practice was articulated around two

matching places of prayer: the church for the parish community, and the

home for the family. Families came together each day around the head of

the household to hold a domestic worship service that mirrored the

Sunday service led by the Pastor. In both places chorales were sung,

with their numerous verses that provided both instruction and a support

for meditation. Any instrument, perhaps an oboe or a violin, could be

used to give the starting note and support the voices. This is why the

works of Pachelbel, and of many of his contemporaries, include chorale

preludes that do not require the use of an organ with pedals and can be

played on household keyboard instruments such as small virginals. in

any case, church organs in central and southern Germany were seldom

large. Like Frescobaldi and Bach, but unlike Buxtehude and Grigny,

Pachelbel had access only to relatively small organs: twenty-seven

stops on two manuals and pedal in Erfurt, a mere fourteen stops on two

manuals and pedal at Nuremberg. Both were well-proportioned small

instruments, although different in character. The reed chorus at Erfurt

and the mixtures at Nuremberg, and the highly individual sounds they

produced, act as a reminder that today's performers should aim, first,

to extract the full character of the elegant, delicate melodic arches

of Pachelbel's arias and chorales, rather than seek large-scale dynamic

contrast.

Pachelbel's geographical situation, midway between Vienna and Lubeck,

was mirrored in his musical situation, equally distant from the

harmonic subtleties of Richter as from the passionate vehemence of

Buxtehude. Through his music Pachelbel appears not as an eloquent

orator but as a specialist in intimate confidences. Often drawn towards

a soft and meditative style, Pachelbel was apparently satisfied with

the limited resources provided by his small instruments and sought to

cultivate neither the dramatic contrasts of the stylus phantasticus,

the enticements of chromaticism nor excessive ornamentation. A born

melodist, he directed his skills to the elaboration of subtle webs of

counterpoint based on pure, almost stark lines, although his ingenuity

is masked by the perfection of the writing that seems to flow

unimpeded. Clearly, Pachelbel inherited the great southern tradition

initiated by Frescobaldi and passed on by Kerll, Poglietti and

Froberger.

Pachelbel's art found its fullest expression in his treatment of the

chorale. He mastered all the forms current at the time for setting

chorale melodies, and generally presented the chorale unadorned in a

clearly recognizable form (the melismatic chorale was developed by

Buxtehude and, especially, Bach). His seventy-five chorale preludes

present a wide range of approaches, all designed to sustain musical

interest. Although some pieces use the ancient two-voice bicinium

technique, most are written in three or four voices; to meet the

requirements of the liturgy, the chorale melody is usually heard

unornamented in the soprano, or in long note-values as a cantus firmus.

However, Pachelbel is never restricted by formula, and the melody

sometimes moves to the tenor or the bass, or is enriched by a delicate

ornamental mantle. The accompanying voices incorporate fragments of the

chorale in augmentation or diminution, or sometimes in imitation,

recalling the fugal style at the heart of Pachelbel's art; fugue, after

all, amplifies and solemnizes the musical discourse by multiplying the

appearances of a single motif. Each phrase of the chorale is thus

introduced by a short fugato, or a preceded by a fugal preamble. Above

all, Pachelbel was drawn to composite structures, where all the

resources of his musical language could be used to illustrate the

spiritual atmosphere of the chorale: sorrowful chromaticism, passing

dissonance, delicate arabesque-like figures or expressive rhythmical

formulae. His variations on chorale melodies clearly served as a model

for the young Bach in his organ partitas.

Pachelbel's organ fugues and ricercares reflect the growing interest of

Baroque musicians in the learned world of dialogue and formal

elaboration, and their tendency to underline the theatrical aspect of

the musical discourse through the development of a single underlying

motif, the "subject" — at a time when, following the work of

Descartes, the focus was on the complexity of the "thinking subject."

In his three ricercares, Pachelbel provides an impressive demonstration

of his compositional skill, applied with more freedom in his fugues,

which include twenty-six isolated fugues and no less than ninety-five

fugues on the Magnificat (in fact, these fugues were for use with the

German Magnificat, or were based on free themes, rather than on the

actual themes of the Magnificat). They create a marvelous world of

sound and poetry and display Pachelbel's never-failing powers of

invention. Although the composer was probably not aware of it, his

fugue subjects define the various elements of his character and

constitute the fragments of a musical self-portrait that reveals a

melancholy side to his nature that sometimes tends, towards pathos.

Two sons, Carl and Wilhelm Hieronymus were also organists and composer,

the former emigrating to the New World and dyimg in Charleston, S.C.

Francesco Onofrio

Manfredini

(1684-1762) Much that we know of Francesco Onofrio Manfredini is

supposition and assumption. Indeed, apart from a few landmarks in his

career, he was obviously not of such significance as to merit

documentation. He was born in Italy in 1684, probably to a musical

family. He did take lessons in violin from the great Torelli, and must

have become a fine violinist, as we know that he held major playing

posts in Bologna. As a composer he left very little, with just 43

published works and a handful of manuscripts. We do know that he became

the head of music at St. Philip's Cathedral in Pistoia in 1727, where

he remained until his death in 1762. This makes it odd that he did not

leave a wealth of sacred music, or was it simply destroyed after his

death.

We do know that Manfredini composed oratorios, but only his orchestral

works remained in the repertoire. His groups of Concerti Grossi and

Sinfonias show a highly accomplished composer, well versed in the

mainstream Italian school of composition. Above all they are replete

with attractive melodic invention.

The group of twelve Concerti Grossi were published in 1718, and

dedicated to Prince Antoine, which may indicate that he was in the

Prince's service in Monaco. That would fill in a gap from 1711 where

Manfredini 'vanished' from the musical map. Each concerto is in three

movements, and while the composer does add a few variants, they are

basically in the fast - slow - fast format. Each of the movements is

brief, some lasting little more than half a minute. That allows for

little more than the statement of a melody, and while these are always

most pleasant in their nature, it is the rhythmic vitality that affords

them a ready attraction. They are scored just for strings, and in the

main are not concertos, as we now know them, but simply symphonic

movements. There are exceptions, such as the fiendishly difficult solo

violin writing in the final movement of the sixth, and the opening

movement of the seventh.

It is music calls for considerable dexterity among the musicians, with

little room left for interpretation. The work has largely become

popular for the Christmas pastorale, which forms the twelfth concerto.

Adagio

· Kanon & Gigue · Concerti grossi

· Alla rustica (Deutsche Grammophone , 1972)

The Italian

composer and violinist Arcangelo

Corelli

exercised a wide influence on his contemporaries and on the succeeding

generation of composers. Born in Fusignano, Italy, in 1653, a full

generation before Bach or Handel, he studied in Bologna, a

distinguished musical center, then established himself in Rome in the

1670s. By 1679 had entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden,

who had taken up residence in Rome in 1655, after her abdication the

year before, and had established there an academy of literati that

later became the Arcadian Academy. Thanks to his musical achievements

and growing international reputation he found no trouble in obtaining

the support of a succession of influential patrons. History has

remembered him with such titles as "Founder of Modern Violin

Technique," the "World's First Great Violinist," and the "Father of the

Concerto Grosso."

The Italian

composer and violinist Arcangelo

Corelli

exercised a wide influence on his contemporaries and on the succeeding

generation of composers. Born in Fusignano, Italy, in 1653, a full

generation before Bach or Handel, he studied in Bologna, a

distinguished musical center, then established himself in Rome in the

1670s. By 1679 had entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden,

who had taken up residence in Rome in 1655, after her abdication the

year before, and had established there an academy of literati that

later became the Arcadian Academy. Thanks to his musical achievements

and growing international reputation he found no trouble in obtaining

the support of a succession of influential patrons. History has

remembered him with such titles as "Founder of Modern Violin

Technique," the "World's First Great Violinist," and the "Father of the

Concerto Grosso."