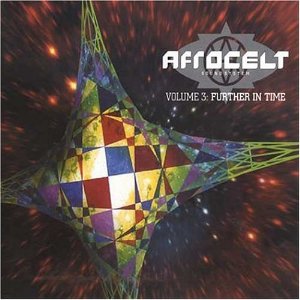

| Artist: | Afro Celt Sound System |

| Title: | Volume 3 - Further in Time |

| Released: | 2001.06.18 |

| Label: | Real World |

| Time: | 70:41 |

| Producer(s): | Simon Emmerson |

| Appears with: | Peter Gabriel |

| Category: | Pop/rock |

| Rating: | ********.. (8/10) |

| Media type: | CD |

| Purchase date: | 2001.06.18 |

| Price in €: | 16,71 |

| Web address: | www.afrocelts.org |